Minority representation cannot be ignored in the classroom

It was 8:31 in the morning when I walked into my virtual class with the click of a button.

While reflecting on my tardiness of sixty seconds and trying to orient myself to what was already happening in class, I overheard my peers discussing our newest novel assigned in a previous period of IB English. This an international program, and as a result the course offers a diverse sampling of world literature. The award-winning text we were starting, Purple Hibiscus, was written by a Nigerian woman.

“I’m tired of all these cultural stories, I just wanna read Old Yeller,” lamented one of my classmates.

Suddenly, I wished I had been later.

I have thought a lot about that moment in the time since, trying to understand where he was coming from. While I was thrilled at the chance to read an enriching story of a culture I never experienced, he wanted a more familiar choice, one from his own worldview. This is one of the intellectual dangers of growing up white in suburban America: oftentimes, we don’t know what we don’t know, and when we have the opportunity to grow, we would rather stay with what feels “normal” and “safe.”

Statistically, my classmate is likely not alone in this confession. As a white student in Portage, he makes up 73.4% of the district population. One of the hallmarks of being in the majority culture and having power and privilege is that you don’t often realize that you have something that others don’t because it seems so normal. Because of this, white students don’t often realize they have been represented every moment of their lives. Without that knowledge, increased diversity and inclusion can feel like a threat instead of something for the common good.

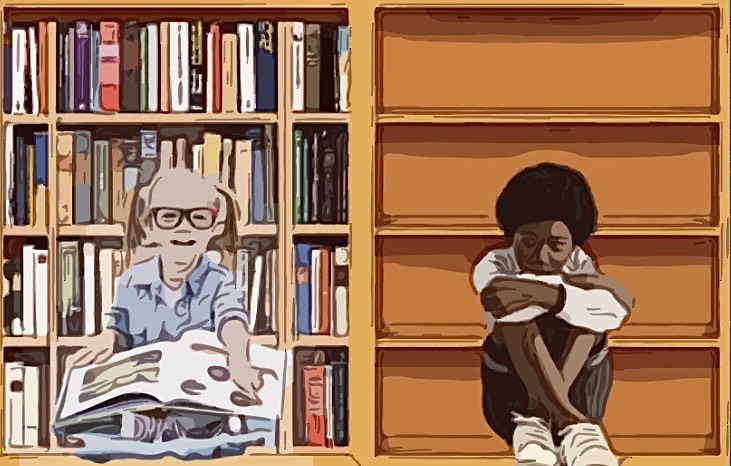

Making up 83.8% of the community as a whole, white children in Portage grow up with guaranteed representation at every turn. They see themselves in a majority of their neighbors, teachers, elected officials, and police officers. The whole community is a mirror, which they already have enough of in the Eurocentric national culture at large. What they need are windows.

Minoritized populations aren’t given this same privilege. We’re forced to live every moment painfully in touch with the reality that we are other. While our white, cisgender peers grow up believing that the world is theirs to take by the reigns, we struggle to make space for ourselves within it.

I spent twelve years alone, acutely aware that I was different. I woke up every day contemplating whether or not I had a future because no matter where I looked, I didn’t see anybody like me living the same lives that my majority-identifying friends were, that their role models were. Their path was clear. Mine had zero visibility.

Stuck in the body of a boy when I was a girl all along, every novel, film, teacher, role model, career, and lifestyle presented before me reinforced the expectation of the gender I was fighting. Minoritized students are rarely given the chance to see ourselves in the world around us. The American Dream is built on the idea that if you can dream it, you can do it, but how can you dream about something that you don’t even know exists? At some point, we learn to face reality: we’ll never be the subject of the story unless we achieve the impossible.

There is hardly a more important place for representation than in school, yet the experience of a white cisgender student and a minority student in the classroom are entirely different. They don’t see themselves in the books they read, the teachers they look up to, the history they study, or the names and pronouns in math story problems.

Minority students are excluded from curricular representation to the point that their existence exists only in stereotypes projected and upheld by the majority. How can these students question this mistreatment if it’s upheld everywhere they look, especially in school, the so-called gateway to knowledge?

One of the easiest classes to diversify would be English, because the class literally centers around studying the stories of others. Despite this, attempts to diversify reading lists have been met with opposition.

According to the American Library Association, 8 of the 10 most-challenged children’s and young adult books in 2019 had LGBTQ+ themes. Critics of these books – adults – asserted that the books should be banned: “to avoid controversy; for LGBTQIA+ content and a transgender character; because schools and libraries should not “put books in a child’s hand that require discussion”; for sexual references; and for conflicting with a religious viewpoint and “traditional family structure”. These books made some parents uncomfortable enough that they sought to remove them even from the hands of the students who are represented in them and who need them the most, ignoring the truth that adding more seats to a table doesn’t diminish the value of any single seat, for it just allows more people to sit together, crafting more conversation and connection.

Research conducted by Brigham Young University suggests that the expansion of curriculum benefits everyone involved. “Expanding curriculum to include a variety of perspectives not only allows educators to discuss views and ideas that are less common or underrepresented, but also provides students a more holistic understanding of the subject area.” The expansion of knowledge isn’t some temporary diversity training that behaves like a bandaid to a lost limb; the expansion of curriculum to include more perspectives can heal the wound impacting generations upon generations.

There’s plenty of room for this work to start right here. The first two years of my high school English education followed this trajectory: Life of Pi, Grapes of Wrath, Romeo and Juliet, Canterbury Tales, L’Morte d’Arthur, Anthem, Julius Caesar, Great Expectations, Midsummer Night’s Dream, Alice in Wonderland. 9/10 white. 9/10 male. 10/10 cis.

Despite the fact that PN is almost a third non-white, practically all of these books were written by white authors and for white readers. The message sent by this is, these are the voices that have value. Most of these books are also outdated and irrelevant, yet we still cherish them, when in reality there are so many newer, more diverse stories to explore. If we celebrate phenomenal multi-representational writing now, those novels can earn their place among the classics we never stop reading. Until we do that, though, we’re going to be left with more and more moments like the one that sparked this reflection in the first place.

After my peer shared his opinion, every second weighed on me. Having been a part of a predominantly white suburban community for my entire life, I can’t say that I was surprised, but I was still disappointed. I had heard these kinds of comments before, but here, in our school’s highest level of coursework, I had hoped that just maybe this time would be different.

I waited, desperately hoping that my teacher would respond, but they never did. They simply laughed alongside my classmates, and we got ready to move on. I sat alone in my disappointment, thinking of my few minority classmates likely sitting solemnly in the same rotten feeling. I couldn’t sit quiet any longer. I knew I had to say something. Before the class could move forward, I unmute my microphone not to confront my classmate, but to share my gratitude for the new text that we were reading.

I wasn’t reckless. I knew I was carrying the weight of those that came before, who acted with grace and class even when they didn’t receive it themselves.

I spoke every word with a smile, concealing the pain and sadness that every minoritized student faces in moments like these.

My classmates’ observation was met with laughter. Mine was followed only by a sharp, excruciating silence.

Senior Kylie Clifton is in her fourth year as a NL staff member. She is a co-editor in chief, having previously served the NL as both a business manager...

Kathy Ha • Apr 6, 2021 at 6:08 pm

Excellent article – insightful and necessary. Great work, Kylie!

Jett Hunning • Apr 6, 2021 at 7:53 am

You’re more of a high school activist trying to advocate against a make-believe problem.

Cerena Read • Apr 5, 2021 at 12:29 pm

Kylie, your work has once again amazed and inspired me. your writing is exceptional! i hope that your peer and teacher will read this and maybe it’ll change something in their head. this story is so important to the future of PNHS. keep doing what you are doing Kylie!! so proud!

Chris Harris • Apr 5, 2021 at 10:36 am

*SNAPS*

Amazing article Kylie! Keep it going girl!