On the first day of school, students received the news of Portage Northern High School’s new phone policy: no cell bell to bell, a rule that had already been in place at Portage Central High School for the past year and that had also been in place at the middle schools for even longer. The policy requires students to keep their phones and other electronics (including headphones) away during class time, though they are still allowed to use their devices during lunch and passing time.

The new guidance sent shockwaves through the student body, but principal Tre Lowder does not see the cause for alarm. “If you look at what our cell phone policy states, it hasn’t changed. It’s been the same,” he says, explaining that before the 2025-2026 school year, teachers had the option of how to interpret and enforce the rule, which led to confusion amongst students and staff alike. “The difference this year is the emphasis on actually being consistent or trying to throw some consistency throughout the building. The inconsistencies [previously created] challenges administratively. Students didn’t really know what was going on sometimes. Parents definitely had no idea what was going on.”

Lowder believes the clear and strong enforcement of the policy will lead to more consistency among classes and fewer disciplinary infractions from students due to cell phones. He adds that the number of referrals in the first month of the last school year was nearly 20, but this school year it has dropped to 3. “Teachers are communicating it. Students are following it. Parents understand it. I think it can help,” he states. “It was [implemented to] eliminate as many distractions as we can so that we can foster a better learning environment.”

Students across all four grades had mixed perspectives on the cell phone policy. Freshman Joel Lawler sees it as positive. “I think it’s a good cell phone policy. I mean, some kids don’t like it because they won’t be on the phone all the time, but I think it’s a way to get off your addiction and pay attention,” he states, adding that since the policy began, “kids have started paying attention more to class.” Though there are positives to not using a cell phone, Lawler wishes there were more flexibility when it comes to family emergencies. “If your mom or dad or parents or anybody in your family sends an important text, you should get to text them back.”

Junior Maxwell Benson views the policy differently. “I think it should be up to the teachers themselves in each of their classes, what they do within their classroom,” he says. Benson also states a positive aspect he has noticed since the policy began: “I feel like I am getting more work done at some point, cause I’m just not thinking about my phone,” he says.

Sophomore Owen Monaghan felt like the change could have been communicated more effectively to students and families. “I feel like I just walked into class and my teachers were talking about it, but in terms of emails, I feel like they could have done better,” he shares.

Senior Aby Nadaud is skeptical that the policy will actually bring change. “I still think people are gonna use their phones,” she says. She also expresses criticism that the cell phone policy doesn’t prepare students for their next steps in life. “You can still use your phone in the real world,” she explains. Her suggestions for improvement include using cell phones in positive ways more like adults do: “I think that we should at least be able to listen to music, and we should be able to have it in case our parents contact us for an emergency,” she says, “and let us still have it when we are done with our work.”

91 students responded to a Northern Light website poll that asked, “Should cell phones and headphones be allowed during instructional time?” 16% said yes, 59% said yes but with some limitations, 13% said no but with special exceptions, and 11% said no. “The words ‘instructional time’ are important,” said senior Danielle Kwon, who participated in the survey. “Having a phone or headphones out when the teacher is teaching is different than using them to listen to music during independent work time or when you’re done with your work.”

Overall, staff are in favor of the cell phone ban. Science teacher Sarah Kozian hopes that it will improve student-teacher relationships. “It makes it so hard for me to get to know my students because our first response when we’re done is to go to [phones]. As an adult, I do it too,” she says. Band teacher William Muffareh agrees, sharing: “I think having a policy that gets students away from their phones and more present with their peers and teachers is a good thing.”

At class meetings on August 28, assistant principal Kelly Hinga shared a story about history teacher Christopher Prom’s students keeping track of how many notifications students get in a class period and how each one is a distraction from learning. While a notification can seem harmless, Hinga’s connection is supported by the research. Most recently, an August 2025 study in the publication New Scientist tells that, “seeing notifications from social media apps seems to throw us off course for several seconds – even if we don’t open them.”

While all teachers are expected to enforce this rule, there will be reasonable exceptions. “I have students who have diabetes who have to keep track of their sugar,” says Kozian. “So they use their cell phone for stuff like that.” Using phones in class can also help English language learners. “Sometimes, we have exchange students and there’s different translation tools that might not work as well on the Chromebook as they might on the phone,” history teacher Allison Grattan explains. For some teachers, the policy only made slight changes. “Last year, the school rule was you could have a phone unless the teachers said you couldn’t, versus this year, you cannot have a phone unless a teacher says you can,” says math teacher Nikki Callen.

Because the policy limits the ability of parents to contact their students during class time, the policy not only impacts the students and staff attending school every day, but families of students as well. Bethany Graham, mother to junior Reese Graham and teacher in the Comstock school district, is nevertheless supportive of the policy. “Class time should be reserved for learning, and since students may use their phone in between classes, that is more than fair,” Graham states. As a teacher of elementary students, she adds that restricting cell phone usage can help students and teachers interact with each other on a more personal level, as she experienced in her own classroom. “The use of a cell phone in class can limit the personal connection, and relationships are key in a supportive learning environment for all,” she shares. Graham tries to foster this same level of connection in her own household, adding that her family has cell phone rules at home, so she doesn’t feel the policy impacts her own student very much.

The ban on cell phones during instructional time is backed by a wide range of research. One experiment at Rutgers University shows that students who use cell phones during instructional time for purposes unrelated to school consistently perform worse on tests and exams. Not only can cell phones have detrimental effects on students in school, but they can also negatively impact sleep schedules and social media strongly affects mental health.

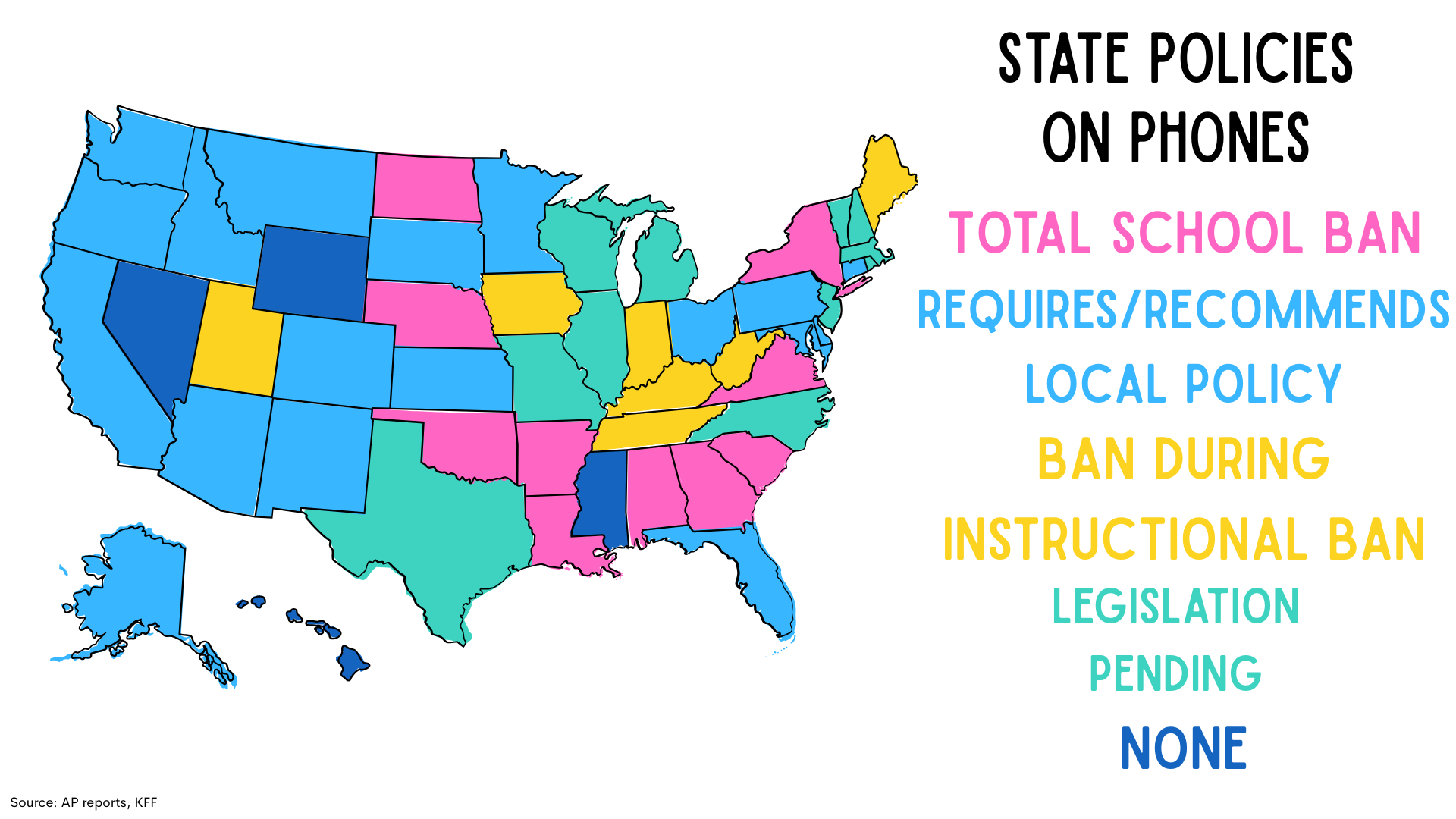

Across the country, lawmakers have begun cracking down on the phone policies in public schools. Only 3 states have no state-wide laws restricting phones whatsoever, and 10 states have implemented complete phone bans at school. In Michigan, lawmakers have gone back and forth on state-wide cell phone legislation, with current momentum being stalled by partisan disagreement on what such a policy should look like.

Schools in the area have implemented similar cell phone policies. Kalamazoo Public Schools did away with cell phones in class in 2024, Schoolcraft Community Schools has a similar no cell bell to bell policy as PN, and Mattawan Consolidated Schools requires students to deposit their phones in a caddy at the beginning of every class period, where they remain until the class is over. Many Northern teachers already have their own versions of phone caddies or “phone jails,” with many having them prior to this year.

Stay tuned to the Northern Light for further coverage of how the no cell bell to bell rule impacts students throughout the year.